Though the Boers have simple habits and few wants, you must not imagine them to be poor. Many of them are very rich, possessing countless herds of cattle and flocks of sheep, and there are many of them whose wool brings them in a very good income. In their homes the Boers are very hospitable, never refusing to entertain a stranger ... They are very fond of music and dancing, and many of them play with much taste on the violin and concertina. This they acquire by ear; their dancing is chiefly confined to reels, and at New Year, when they assemble in great numbers at different houses, they keep up this dancing for two or three consecutive days, not even resting at night.![]() 1

1

A Boer family at home. A young couple is dancing; the man is playing the German concertina while

they dance on the dirt floor. Drawing by John Guille Millais in A Breath from the Veldt, 1895.

An 1899 account by a British visitor, just before the start of the Second Boer War, also describes the Boer passion for concertina music and dancing:

The dancing begins at five in the afternoon to the music of a concertina played by a 'Cape boy', which is to say a half colored man. Everyone appears in their ordinary dress, uncouth, untidy, and slouchy in the extreme. The women almost invariably wear black with, perhaps, a bit of colored ribbon. The men are in corduroys or cheap tweeds, often wearing their 'smasher' hats and shod in heavy veldtschoens, or boots.

No 'square' dances are performed, but one dance is like another - a slow, jumpy, heavy, monotonous whirl, something between an elephantine waltz and a cumbersome polka. The girls sometimes place their two hands on their partner's shoulders and the men clasp the girls' waists with their two hands.

After a few hours of serious jumping about, the room has to be cleared, for, the floor being of earth, a terrible dust is knocked up and, as the doors and windows are invariably closed, the atmosphere becomes thick with floating clouds of dust. Everyone goes out into the stoep and is refreshed by dop (Boer brandy), lemonade, cookies (cakes) and sweets. In the meantime the room is swept and sometimes a calabash of bullock's blood is brought in with which the floor is smeared by the natives. From time to time - say, every two or three hours - this is repeated, so that intervals of dancing, dusty cloudiness, refreshments on the verandah and smearing of the floor succeed one another periodically.

This sort of thing goes on until about 8 in the morning, when everyone gets a bit sleepy. A general adjournment takes place. The women collect in the side room and snatch a few hours' sleep and the men lie down in the wagon house, or under their carts on the veldt, to smoke and rest. At about noon, after a hearty meal, they begin dancing again until late in the afternoon. At last they go home after about four and twenty hours of it and scatter over the veldt to their far distant homes. ![]() 2

2

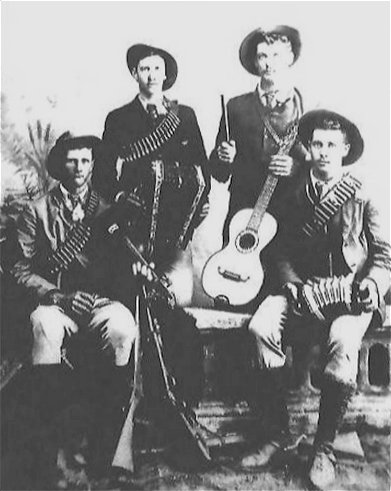

A group of musical Boer soldiers, a few months before the beginning of the Second Boer War.

Amongst the rifles and bullet belts they hold a fiddle, button accordion, guitar and concertina.

The leader of the band was the concertina player, A Jonas. Photo by Hugh Exton, from the

Hugh Exton Photographic Museum in Pietermaritzburg. With thanks to Wilhelm Schultz.

This style of dancing, along with the dust, occurred at the Cape as well, with the Cape Dutch descendants of those who had not made the Great Trek. The following account was written in 1900 about earlier years there:

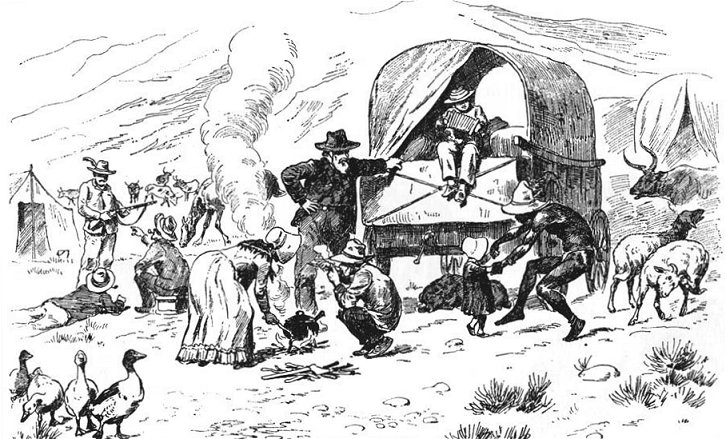

Boer family on a trek to market, late nineteenth century. Note the concertina player on the wagon, and an

African servant dancing with a Boer child. From a late nineteenth century drawing by Heinrich Egersdörfer.

Even dances indoors could occur on a well-greased wagon sail, as in this account of a 1907 wedding:

There was enough commercial interest in the bands that played for these dances that they were recorded on 78 rpm records beginning in the early 1930s. These recordings were made in the prime of playing years for their concertina players, unlike most recordings in Ireland, England and Australia, which were made of ageing players during the late twentieth century folk revival. For this reason, the recordings are startlingly vibrant and danceable, and yet the concertina players who made them were typically born in the 1880s, 1870s and even earlier.

All of the recordings in this chapter are from these old 78 rpm recordings. The Tradisionele Boeremusiekklub van Suid-Afrika (Traditional Boer Music Club of South Africa, or TBK), was founded in 1981 for 'the collection, preservation and enhancement of Traditional Boer Music'. They made it an early goal to digitize, preserve, and distribute these old recordings, and their inclusion in this archive is thanks to this organization and especially the work of Danie Labuschagne, Stephaan van Zyl, and Plato Michael.

Boer dances have many similarities with those of Ireland, England and Australia at this time. The Boers mainly danced the settees (schottische), wals (waltz), polka, and masurka (mazurka), although the country dance, quadrille, and cotillon were not unknown, especially in the nineteenth century. An additional dance that developed in South Africa is the vastrap.

As elsewhere, dance music was initially played on a two row German concertina, called a boerekonsertina in Afrikaans. By the time of the early 78 rpm recordings in the 1930s, most of the recorded players had acquired higher quality English-made Anglo concertinas, a sign of the growing prosperity of the Boers relative to counterparts in Ireland or Australia ... or perhaps a sign that the professional dance bands demanded the very best in musicianship. However, there is a current movement within the TBK to reintroduce the old German two row concertinas that had been so popular before the bands arrived; an example of a modern day player, Stephaan van Zyl, playing the boerekonsertina is included in Chapter 11.

The 1930s saw an explosion of new techniques and styles in Boer music, as the ability to make and distribute recordings inevitably began to change a dancing audience for the music into a listening audience as well. The oldest of the concertina players on these recordings, Faan Harris, Kerrie Bornman and Chris Chomse, played in a style that was essentially a two row octave style, with simple rhythmic melodies repeated for the dancers. Of these three, Faan Harris acquired a three-row Lachenal Anglo and began to experiment with adding chromatic notes, and he also added significant amounts of improvisation to repeated playings of melodies. Boer band musicians in Harris's day were no doubt influenced by imported recordings of jazz music that was, by the 1920s, popular in South Africa. Harris's music was the first step in a wave of developments. Hans Bodenstein and Willie Palm carried this process further, beginning to play in keys other than those of the two 'home rows' on the instrument (which was typically pitched in C/G); they played a number of tunes in the keys of D and A, and yet still played in octaves.

Players like Pietie Prinsloo and Silver de Lange added yet more complexity, devising long fluid and often chromatic phrases that took full advantage of extended range 40 button Anglo concertinas. They also continued to add to the complexity of improvisations. Their tunes were now largely unplayable on the original two row boerekonsertinas of a generation earlier. Since their time, the music has continued to grow in complexity.

These seven names were discussed more or less in birth order; Silver de Lange (the youngest, born in 1904) was 18 years younger than the oldest (Faan Harris, born in 1886). Younger players were strongly influenced by the new sounds of jazz and injected a newer style to the old tunes. This newer way of playing was enabled by the 40 button Wheatstone instruments that were imported an relatively large numbers from England, especially by the middle of the twentieth century.

These developments stand in strong contrast to the situation with regard to dance music in England and Ireland, where the concertina was fast disappearing from newer dance bands, be they céilí or jazz. Only a very few players, like Fred Kilroy, experimented with chromatic music, and most simply gave up. Younger Irish players in the céilí dance era turned away from octave playing and began to play singly and more along-the-row, in order to keep up with the revived reels that had mostly displaced the round dance and quadrille music of an earlier generation. In Australia, pockets of old time dancing continued in certain areas in the 1930s, but without the stimulus of recording 78 rpm records there was no impetus to further develop playing styles beyond what they had been in the nineteenth century. Australian concertina playing continued in a relatively simple, two row style.

The 1930s, when most of the recordings in this chapter were made, mark a high point of Boer music. After World War II, and after the introduction of rock 'n roll, South Africa experienced the same decline in dance and in concertina playing that other countries had seen; efforts to reintroduce dance, and to preserve Boeremusiek, are similar to folk revival activities elsewhere today.

Faan Harris and Boet Steyn playing music on the market square of Krugersdorp,

around 1946. They are standing next to Steyn's 1938 Ford truck.

Photo courtesy of the Tradisionele Boeremusiekklub van Suid-Afrika.

His main recordings were made with Die Vier Transvalers (The Four from the Transvaal), one of the most popular Boer music bands that ever played. Faan Harris was the leader, along with two guitarists (Josephus DaniŽl (Sewes) van Rensburg and Frans Hendrik (Frans) Ebersohn) and one cello player (Hendry Frederick (Bossie) Bosman). They recorded ten tracks in 1932 for the British company His Master's Voice, and the group went on to place second at a 'World Music Competition' in Johannesburg in 1936. After a second recording session in 1937 (for which the recordings are lost), the group broke up. Faan went on to record with other groups, but none have had the impact of the recordings with the Transvalers.

Three members of Die Vier Transvalers, ca.1934. From left to right, Frans Hendrik Ebersohm,

Faan Harris, Henry Frederik Bossman, and Peter Bosman. Bosman was not a member of the group.

Harris played a three-row C/G Lachenal concertina. Relative to the playing of recorded contemporaries in Ireland, England and Australia, Harris's playing was more complex, and utilized all three rows of this concertina.

The waltz Eileen Alannah was written by American composer John Rogers Thomas in 1873, and became a global hit, well known in Ireland, England and Australia (see discussion, Chapter 5). He plays this tune in the key of G, starting on the C row but using cross-row fingering on the G row for higher passages, and uses the top for frequent chromatic notes used in short chromatic runs. Frequent use of partial chords is made on both the left and right hands. At times, he adds a bellows shake to long notes, to give them more character. Through all this, however, Harris is basically an octave player, and nearly every note is played in octaves. This is concertina music of the highest quality for his day, and yet is still strongly rooted in the older style of play.

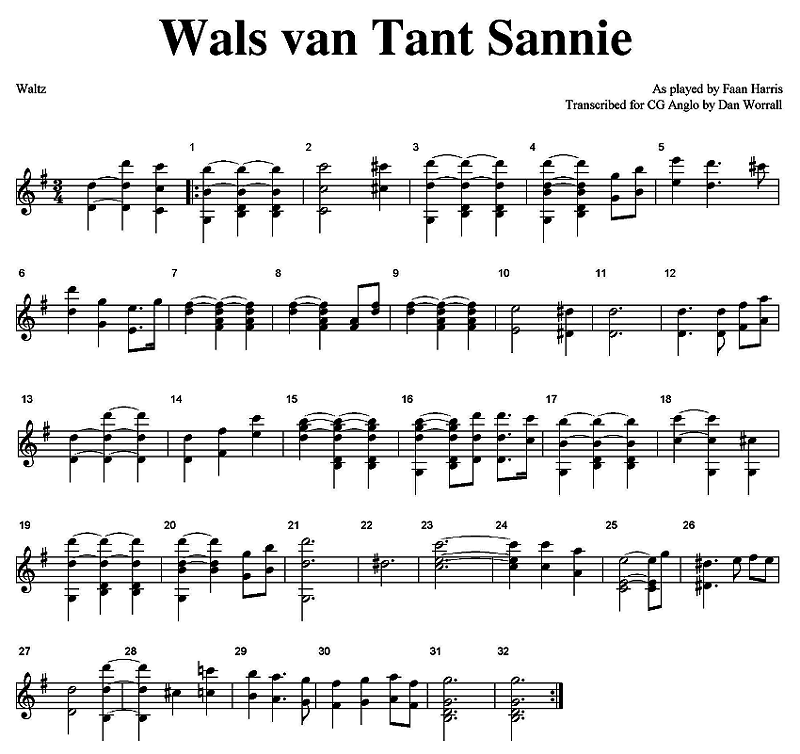

Wals van Tant Sannie (Aunt Sannie's Waltz) was named for Harris's aunt, but is actually the American tune The Shannon Waltz. This waltz seems to have been first recorded by the East Texas Serenaders in 1926 in Texas. The Serenaders learned it and a number of other unusual tunes from a traveling fiddle player only known as 'Brigsley.'![]() 6 Faan Harris's version of this waltz was recorded only four years after the piece was first recorded in Texas. How the tune made its way to South Africa is not known, but recordings of the Serenaders were quite popular, and such recordings of the latest dance music were circulated globally. As Wilhelm Schultz has pointed out, Boers freely imported sheet music and later recordings from abroad throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, especially of American minstrel tunes, popular songs, and dance tunes from Europe and America. These imports were often given new lyrics and renamed in Afrikaans.

6 Faan Harris's version of this waltz was recorded only four years after the piece was first recorded in Texas. How the tune made its way to South Africa is not known, but recordings of the Serenaders were quite popular, and such recordings of the latest dance music were circulated globally. As Wilhelm Schultz has pointed out, Boers freely imported sheet music and later recordings from abroad throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, especially of American minstrel tunes, popular songs, and dance tunes from Europe and America. These imports were often given new lyrics and renamed in Afrikaans.

The East Texas Serenaders were particularly known for their bluesy rags and waltzes, and Faan Harris masterfully adapted this modern tune to his three-row Lachenal Anglo. Such heavily chromatic twentieth-century material spelled the end of popularity for the diatonic Anglo-German concertina in much of the world, as the typical two-row C/G Anglo could not play most of the required half steps. The situation was to be much different in South Africa, as demonstrated by this piece and by the preceding Eileen Alannah. Harris embraced these new chromatic touches, playing them with relish.

Wals van Tant Sannie is played in the key of G, as can be seen in the adjacent transcription of the A part of the tune. Harris played it mostly in octaves in a cross-row fashion, with lower-pitched parts of the melody played on the C row, and higher notes on the G row. Frequent chromatic notes are played on the top row, in octaves where possible. The chromatic half steps are found in measures two, five, ten, twenty-two, twenty-six, and twenty-seven. He employed an impressive array of rich chords and triple octave notes (three notes, each an octave apart) in this tune, and used the bellows shake technique - albeit sparingly - on some of the long notes in the piece. Wals van Tant Sannie is a superb and complex concertina arrangement.

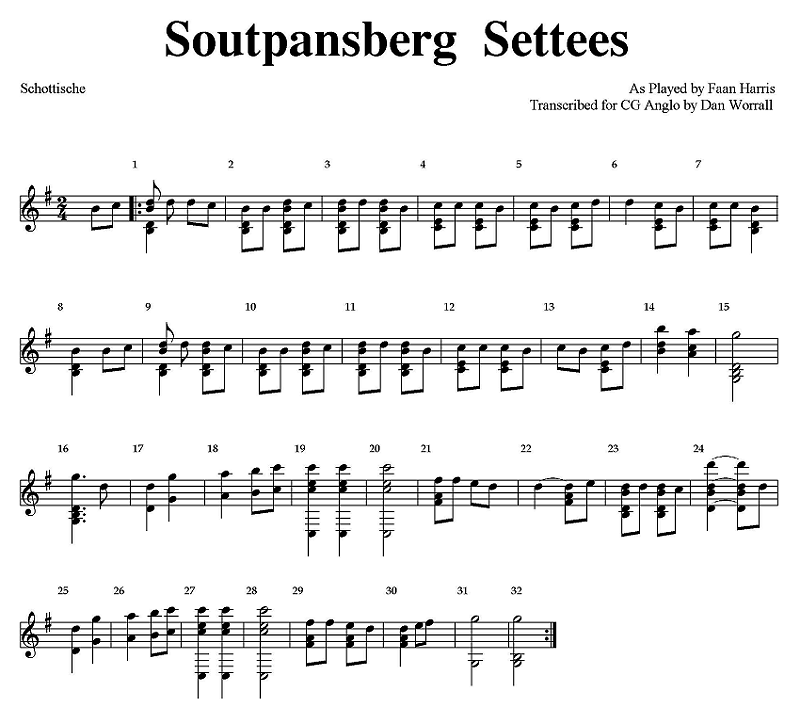

The Soutpansberg Settees, a schottische, was written by Harris during a trip to the northern Transvaal that he took with a friend, where they slept on the open veldt in a homemade tent. Soutpansberg is the name of a mountain range in that area. This tune is played in the key of G and mostly on the C row of his C/G concertina, but he switches to the G row in higher passages - such as measures fourteen and fifteen, and thirty-one and thirty-two - and in measures with octave runs (measures sixteen through most of eighteen). Harris plays it wholly on the two rows of his concertina, without the chromatic complexities of the above two waltzes. Examples of cross rowing for fluidity in melody can be found in the last notes of measures one, two, and twenty-three, where the fingering drops down to the G row to keep a phrase on the pull. Because strings of eighth notes in the melody are alternately chorded, this cross-row fingering helps keep the passages all in one direction, facilitating the repetitive left hand chords. Sean Minnie, who plays this tune today, mentions another reason for cross-row fingering:

Anna Pop Settees is another schottische. It is played in C, mostly on the C row, except for some places where he drops to the G row to pick up alternate eighth notes to preserve unidirectional passages. There are no chromatic notes.

Kromdraai Mazurka is thought to have been named for a gold mine and associated town just north of Pretoria, near Krugersdorp, where Harris once lived. It is played in the key of G, mostly in octaves, heavily cross-rowed with a number of chromatic runs. Mazurkas have remained popular in South Africa to a greater extent than in the other three concertina countries of this report.

The Rooidag Toe Polka (roughly, Until Daybreak) is played in the key of G, in octaves and is extensively cross-rowed. It is played entirely on two rows, with no chromatic runs.

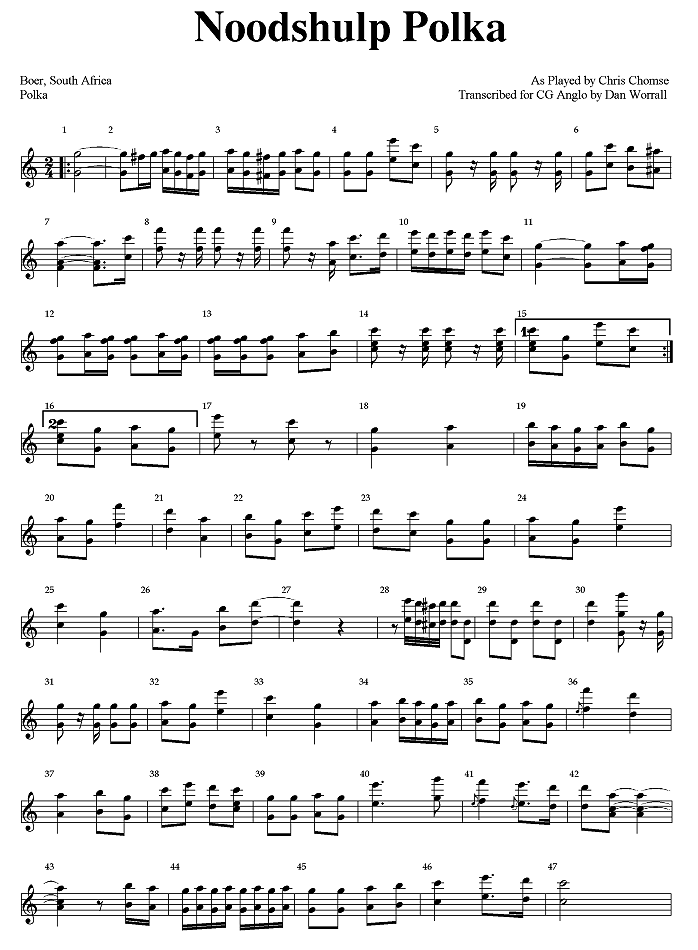

Chris Chomse. Photograph with thanks to the

Tradisionele Boeremusiekklub van Suid-Afrika.

While still in South Africa, he formed a band, Die Lydenburg Vastrappers, named for the town in which the members lived. Besides Chomse on concertina (the group's leader), there were Klaas Alexander Erasmus on clarinet, Geertruida Zacharyda Magdalena (Baba) Winterbach (nee Prinsloo) on piano, and her husband Christiaan Willem (Chris) Winterbach on guitar. The group recorded in 1934 on the Singer label.

This group was unusual among Boeremusiek bands because of its clarinet, and its smooth rhythm. Both accounts give the group a very German sound, not surprising given their leader's German roots. It may be the closest recording we have to the sound of continental German music played on the concertina, because the two and three row concertinas were quickly replaced there by much larger Chemnitzers and Bandoneons.

The Noodshulp Vastrap (possibly, the First Aid Vastrap) is played almost entirely in octaves. Chomse seems to have played a three row Bb/F Anglo that allowed him to play with a clarinet in his band; for the purposes of the transcription, this tune has been transposed up a note in order to match the pitch of a C/G Anglo, the system most commonly played today. (Please note that modern Boer players can play in a great number of keys on their extended keyboard 40 button C/G Anglos, including Ab, A, Bb, C, D, Eb, F and G). He plays the tune in the key of F (G in the transcription), entirely in octaves. The tune is 'crooked' as played - there are only fifteen bars in the A part, and thirty-one in the B. Like most Boer players in the bands of the 1920s and later, Chomse played with a guitar that functioned as a rhythm backup. With this backup he could hold long notes, whereas a solo player would have to punctuate in every interval to keep the rhythm going for the dancers. Chomse took full advantage of his guitar backup, and clearly didn't care about the effect of long pauses on the number of bars in this polka, so long as the tune had an even number of beats.

There are prominent chromatic notes in the second, third, and sixth measures - this is clearly a twentieth-century tune, or at the very least a twentieth-century arrangement. Dissonant chords in measures eleven through thirteen are made on the pull on the C row, using the pull F on the top row (as transcribed). Like most Boer tunes, there are only a few grace notes in this polka; these are all in the B part. As in Australian and early Irish playing, the playing and rhythm of the tune were executed in a relatively simple manner for the purpose of dance. Chording is likewise simple, comprised of just a few third intervals, or of the dissonant second intervals already mentioned.

The Baba Wals (Baby waltz) is played in the key of Bb, mostly on the Bb row but with some chromatic notes. It is mostly played in octaves.

The Bosveld Polka (Woodland Polka) is played in the key of F on his Bb/F concertina, all on the F row, and mostly in octaves. Bosveld is a town in Limpopo.

The Mampoer Seties is played in the key of Bb, mostly in octaves. It is a simple tune, and Chomse makes effective use of phrase-ending partial chords on the right hand. Mampoer is a white spirit made from fermented fruit, and is the Boer equivalent of moonshine.

The Wissel Polka (wissel means 'exchange') (Woodland Polka) is played at first in the key of Eb, then modulates to Bb in the B part. Chomse uses extensive cross-row fingering between the Bb and F rows.

His family was deeply musical. Kerrie's grandfather, father and uncle were all concertina players, which brings the family experience back to the very beginnings of the instrument. He began to play for dances by 1904, and at times played for the English for their Lancers quadrilles. At this time he played the German concertina, as did most in Boer South Africa during this time of poverty. He left South Africa to work on the Paris-Dover railway during the depression, then returned to work in the diamond fields at Bakerville.

At this time he was part of a renowned Bornman family band, but the group was never recorded. He did make two recordings however in the 1930s, which are included below. They are of interest as the only boerekonsertina (two row German concertina) recordings made in the early days (by that time most preofessional and semi-professional players had purchased Anglo concertinas), and thus are our clearest link to earliest styles of playing in South Africa. It was only in the late 1950s that Bornman was again recorded, at the age of 67. Bosman Kock, a local broadcaster, was searching out old Boer concertina players to record. By this time, Bornman had an English-made Anglo concertina, and played his concertina with his son Ricardo on guitar. Bornman died at the age of 77.

Kerrie Bornman and his son Ricardo, ca.1958. Photograph with

thanks to the Tradisionele Boeremusiekklub van Suid-Afrika.

The two pieces that Kerrie Bornman recorded in the 1930s are a waltz, Oom Tien se settees. Bornman plays both pieces in the key of D on a two row German concertina that most likely was pitched in G and D. In the schottische, he plays often in octaves, creating third interval partial chords on the left hand by adding a note up from the lower octave note. He also adds a bass note for an oom-pah rhythm. The waltz begins with an opening phrase in octaves, followed by similar oom-pah chords on the left accompanying a right hand melody, with occasional octave phrases that occupy both hands.

Ou Wessel se Settees (Old William) is a schottische in the key of D, in which Bornman is playing on a two row German concertina (Boerekonsertina) that is pitched in C/G, like that of his earlier recordings.

The Pietersburg Mazurka is played in the key of G; the low octave in this piece indicates that he is playing it on a G/D German concertina. It is a fairly simple but charming tune, mostly in octaves.

Four miles from Benoni [which lies about 30km east of Johannesburg] we passed through a straggling hamlet. Then another mile under the stars with no sign of life about us.

"D`you see the light?" said our guide at length. "That is the hall". Away to the left a solitary gleam sparkled in the darkness. It grew in brilliance as we approached, and finally resolved itself into two prodigeous gas lamps over the door of a large, squat building. This was the hall. To come across it thus planted down in the open veld was like finding a crocus blooming amid the snowy wastes of Kamchatka. We parked our car, paid ten shillings each at the door, and walked inside.

Under the light of a dozen gas flares half a hundred couples were gallivanting gaily. The band sat in a far corner. It mustered only five players, but the joyful noise they made could be heard far into the night. A woman thumped enthusiastically on a piano that bore the marks of many a stern encounter. The melody was being powerfully coaxed from a concertina, while the rhythmic support was being accorded with gusto by two guitars and a banjo. Some of the musical effects had apparently been rehearsed; others definitely had not. The band continued playing until the "captain of the team" thought the dancers had had enough. Then he clapped his hands, and the music came to a summary stop. A "vastrap" was followed by a "wals", a "polka" and a "tikiedraai lancers", all set to favourite Afrikaans melodies, and then the whole process was gone through again. This was the genuine article without a doubt. The dancers were in their Sunday best. The gentlemen wore notty blue suits, and the ladies coloured costumes that beggared description. There were no formalities as to introductions, and so forth. You merely approached a girl, clasped her round the waist, and whirled her round the hall. One young fellow varied this procedure by trying to snatch a kiss from an elderly woman. She slapped him cordially in the face, and referred him to her daughter, a dainty little blonde, around whom navigated beaux were clustering like bees around a honey pot. He dutifully took his place in the cue.

Among the trippers might be seen some styles which savoured of the ballroom and others which smacked definitely of the barn dance. The vertical and horizontal arms, and the gracefully cocked head, the stiff leg, the slow shuffle, the gay gallop and the backveld blues - all were there. I saw one of those arms come into violent contact with a passing nose. The owner of the arm spent several minutes to explain it away.

When the interval came round, coffee was served to everybody. Most of the girls smelt it first. After I tested it, I understood why. Every now and then, too, our guide would seek us out to inform us that he was a "cultured gentleman" and that he did not generally come in contact with such people. These protestations become more and more tearful as the evening drew on. Before we left he pulled a bottle from his breast pocket and demonstrated to us just how he was bidding dull care begone. Nor was he alone, it seemed , in this. We bade him good-bye before the general joy had become quite unconfirmed, but the sounds of revelry pursued us far into the night.

The "Sheepskin" Band came to Johannesburg last Tuesday (22 July) and recorded a dozen numbers for posterity.

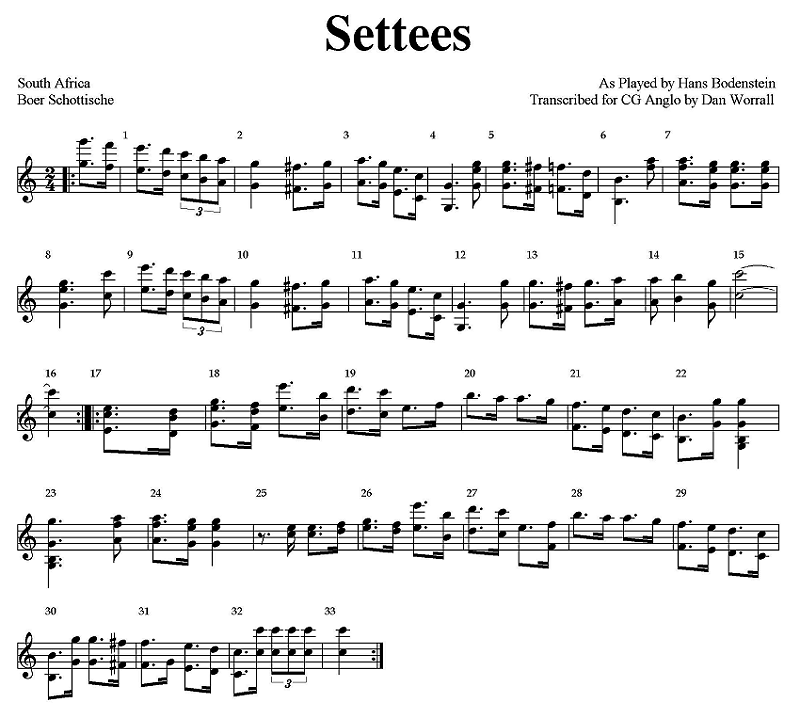

Die Vyf Vastrappers in 1926. Hans Bodenstein is second from left.

Photograph with thanks to the Tradisionele Boeremusiekklub van Suid-Afrika.

The recordings were released on Regal, a less expensive subsidiary label of Columbia Records UK. The band disbanded in 1934. Bodenstein died in 1946 in Benoni, but piano player Carolina Leeson lived into the 1980s.

Bodenstein played a three row C/G Wheatstone concertina. An Untitled Settees (Schottische) is a fine example of early Boer playing, and is playable on a two-row C/G concertina. As the adjacent transcription shows, Bodenstein plays this piece in the key of C, using a cross-row technique where he plays the lower phrases on the C row and the higher phrases on the G row. The tune is played nearly completely in octaves. The sparse chords are partial and easily built, as they primarily consist of simple third intervals down from the top octave (right hand) melody notes. Building the partial chords on the right hand contrasts with the technique used by English players like William Kimber, who typically chord on the left; this right-hand chording imparts a continental European sound to the music. The transcription of the A part represents his second time through the tune; in his first time through, those partial chords were left out, and the playing was purely in octaves.

Bodenstein follows the melody in a cross-row manner as it weaves between the C and G rows. For example, measures one, two, and the first half of three are played on the G row, and then the fingering moves to the C row through measure eight, except for a single excursion back to the G row for the F# in measure five. The B part similarly moves between the two rows.

One characteristic of Bodenstein's playing, evident in all the pieces here, is his jazz-like improvisation of the melody line, in successive repetitions of the piece (the first line is played 'straight'). This takes considerable skill, and the extent of this improvisation is not encountered amongst early recorded players in the other three countries of this study. It seems reasonable to assume that the rise of improvisation was linked to the jazz recordings the Boers were hearing in the 1920s.

Tweestep Sammie Settees (Two-step Sammy's Schottische) was composed by Bodenstein and named for a man named Sam Warren. Warren and his wife often danced to the Vastrappers' music. The tune is played in the key of D on his C/G concertina, fully in octaves. This is somewhat unusual, as D is not one of the two home rows of the concertina that Bodenstein played; it illustrates both his mastery of the instrument and a growing trend to cross row fingering utilizing all three rows of the newer Anglo concertinas.

Untitled Waltz is similarly played in the key of D, with a few chromatic runs.

An Untitled Polka is a relatively simple tune in the key of G, played in octaves, and almost all on the G row. It is decorated with many partial chords played in the characteristic style on the right hand.

Die Fluister Waltz (The Whisper Waltz) is a more complex tune, played in the key of C, again in octaves, with many chromatic runs.

Willie and Lettie Palm. Photograph with thanks to the

Tradisionele Boeremusiekklub van Suid-Afrika.

Oom Koos se Mazurka (Uncle Koos's Mazurka) is played in G, in octaves, with some right hand partial chords.

Vergeet Nie (Never Forget) is a waltz in the key of C, played in octaves and in a cross row manner, with a few brief chromatic runs.

Kom ons dans (Come let's dance) is a schottische played in the key of A. This is a rarity amongst early players, and was not seen in the recordings from other countries of this study. It is played in octaves, with considerable amounts of cross-row fingering required. It is deceptively simple, but the style of fingering is complex because of the unusual key. Playing tunes in non-home keys is a hallmark of both early and modern Boer playing.

Mampoer Polka is played in the key of D. Another version of the polka is played by Chris Chomse, above. Mampoer is a white spirit made from fermented fruit, and is the Boer equivalent of moonshine.

Pietie Prinsloo in 1932. Photograph with thanks to the

Tradisionele Boeremusiekklub van Suid-Afrika.

Prinsloo had no children, but doted on his brother Henry's. Koekoe my hartjie se Seties (Koekoe my Heart Schottische) is named for his brother's oldest daughter Koekoe. The tune is played in D in what seems to be a C/G three row Anglo. He plays in octaves in a very fluid style in long melodic runs that attests to intricate cross-row fingering across all three rows. This is technically proficient playing indeed.

Ek hou my Iyf soos 'n ou fisant (I act like an old pheasant) is a polka played at a very brisk tempo, only partly in octaves, in the key of D.

Silver de Lange in 1932. Photograph with thanks to the

Tradisionele Boeremusiekklub van Suid-Afrika.

De Lange's music is complex. There is frequent use of chromatic phrases, and complex improvisations are introduced in successive repeats of the tune. His phrasing makes abundant use of cross-row techniques on an extended range Anglo - perhaps a 40 button Wheatstone. For this reason, many of his tunes require more than can be delivered on the normal three-row, 30 button Anglo. When the Wheatstone Concertina company wished to redesign parts of their Anglo concertinas (South Africa was a big market for 40 button Wheatstone instruments in the early twentieth century), they paid de Lange's way to London for consultation.

Militaire twee-pas vastrap (The Military Two-step Vastrap) was rescued by members of the TBK from a chipped 78 rpm disc by painstaking reconstruction, and the results are well worth their effort. It is played in C on a C/G Anglo concertina. It is mostly played in octaves, and with considerable amounts of cross-row fingering as well as a few chromatic notes. Following a first playing of the straight melody, de Lange then plays successive passes with a considerable amount of improvisation.

Warm Pattat Polka (The Hot Sweet Potato Polka) is played in the key of D on a C/G concertina, and like all of his pieces contains a significant amount of improvisation in successive repeats of the tune. A 'hot sweet potato' is Boer slang for a fetching and spirited young woman.

Mielieblare Settees (Maize Leaves Schottische) is played in the key of G, mostly on the G row except for lower parts of the B part, in octaves. There are numerous chromatic notes added to spice up the melody, and there is a considerable amount of improvisation.

Het Jy My Nog Lief (Do You Still Love Me?) is a waltz, played in the key of G, with significant amounts of chromatic notes and improvisation. De Lange uses the bellows shake to good effect in long notes.

Die Hele Nag Deur Vastrap (The Whole Night Long Vastrap) is played in the key of C, in octaves, and makes full use of an extended range Anglo keyboard in delivering the tune's complex phrasing.

2. 'Boers great dancers', Omaha Daily Bee (Nebraska), December 14, 1899, p.4.

3. Beatrice M Hicks, The Cape as I Found It (London: Elliot Stock, 1900), p.129.

4. Gordon Le Seur, Cecil Rhodes, The Man and His Work (New York: McBride, Nast & Company, 1914), pp.157-158.

5. 'Boer Courtship,' The Otago Witness (New Zealand), November 6, 1907.

6. Keith Chandler, 'The East Coast Serenaders', extended notes to document release: Musical Traditions, article MT020 (1998), http://www.mustrad.org.uk.

| NEXT |